Renter households have been disproportionately harmed by the financial fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, but this financial distress was also highly geographically concentrated at the neighborhood level, according to a new paper published as part of the Housing Crisis Research Collaborative [1].

New data from the Joint Center for Housing Studies [2] revealed renters living in communities of color, and in high-poverty, lower-income, and lower-rent neighborhoods were more likely to experience financial distress. The paper also finds that emergency rental assistance (ERA) was similarly concentrated in these neighborhood types, indicating that ERA generally reached the neighborhoods with the greatest need.

In "The Geography of Renter Financial Distress and Housing Insecurity During the Pandemic [3],” JCHS uses restricted-access data from the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey containing detailed geographic information about where respondents live. Data found that 23% of renters lost employment income in the month before they were surveyed between April 2021 and February 2022, while 15% fell behind on their rent. These rates vary substantially by neighborhood type.

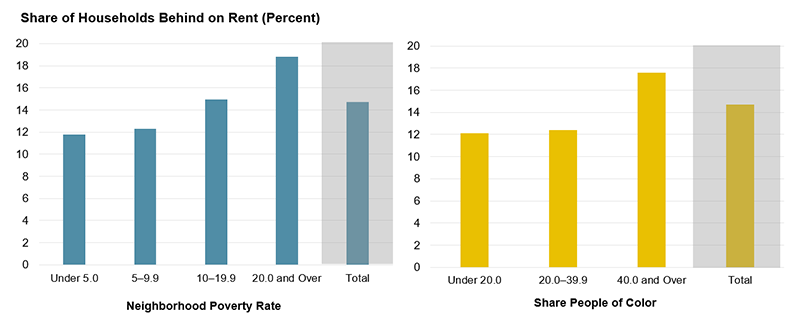

Some 19% of renters in higher-poverty neighborhoods (where more than 20% of the population lives in poverty) fell behind on their rent, compared with 12% living in lower-poverty neighborhoods (where under 5% of the population lives in poverty). Likewise, financial distress was more common in lower-income and lower-rent neighborhoods, and neighborhoods with higher shares of people of color.

Renters in High Poverty Neighborhoods and Communities of Color Were More Likely to Fall Behind on Payments

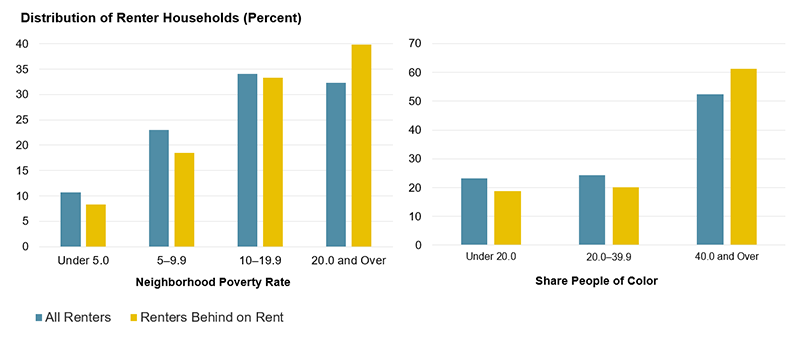

Because renters themselves are concentrated by neighborhood, these differential rates translate into a substantial concentration of financial distress. Two-fifths of renters behind on their rent lived in higher-poverty neighborhoods, while just 8% lived in lower-poverty neighborhoods. Meanwhile, enduring patterns of segregation, also a product of longstanding discrimination in housing markets, have contributed to the spatial distribution of employment income losses and rent arrears. Some 61% of households behind on their rent lived in communities of color (where at least 40% of the population was people of color) while just one-fifth lived in neighborhoods where the share of people of color was under 20%.

Rental Arrears Were Concentrated in High-Poverty Neighborhoods and Communities of Color

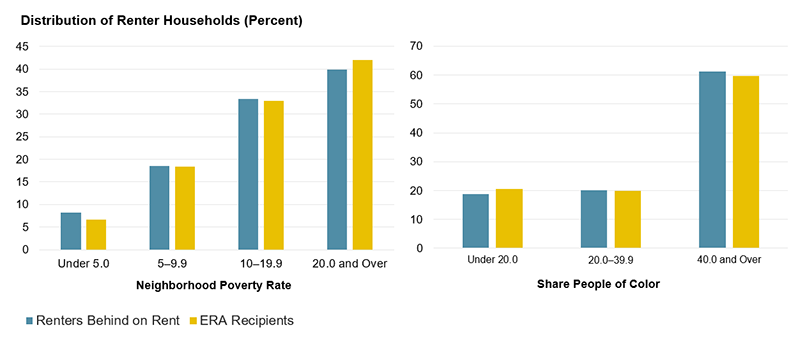

Given this concentration of rental arrears in certain kinds of neighborhoods, JCHS also assess the extent to which ERA reached neighborhoods with the greatest need. JCHS found that the share of renters who applied for and ultimately received rental assistance was similarly concentrated in neighborhoods experiencing the greatest financial difficulties. For example, about two-fifths of ERA recipients lived in higher-poverty neighborhoods, while three-fifths lived in communities of color — comparable to the concentration of renters behind on their rent.

Emergency Rental Assistance was Largely Concentrated in Neighborhoods with the Greatest Need

According to JCHS data, the geographic context and concentration of renter financial distress is important to understand because it has likely shaped rental property ownership and renter instability in specific neighborhoods. Owners of properties where many tenants are behind on rent might defer maintenance and essential payments like mortgages, utilities, and property taxes. If these units are concentrated in higher-poverty neighborhoods or communities of color, that disinvestment might also be concentrated in these neighborhoods. Financial distress in these neighborhoods has the potential to increase housing instability, which could negatively impact neighborhoods by rupturing social ties and destabilizing properties.

To read the full report, including more data, charts and methodology, click here [2].